In the historical present: an essay in tenses

Macushla Robinson and Anna Harsanyi

It begins with the audacity of a name: not a new school, The New School. The name evinces the bold hope that the school will never grow old. The New School’s centennial presents a paradox; when does something stop being ‘new’? What does it mean for an institution to carry this moniker forward in time? Will the word ‘new’ cease to define the moment in which we live, just as ‘modern’ has lost its capacity to denote an ever present? If, as Giorgio Agamben writes, the contemporary is “a singular relationship with one’s own time, which adheres to it and, at the same time, keeps a distance from it” then we must be, paradoxically, out of sync with the new at the very moment that we commemorate it.

It is tempting to mark institutional histories along a straight line; we could easily list a sequence of events from the school’s 1919 founding in response to Columbia University’s censure of professors who opposed America’s entry into the first world war, followed by the construction of its first building (designed by Joseph Urban in 1930), The University in Exile in 1933, and a growing list of mergers, expansions and consolidations from the integration of Parsons (1970), to Milano (1975), Lang (1985), Mannes (1989), The School of Drama (1994) and the College of Performing Arts (2015). With its founding mythos of innovation and rejection of institutional norms, the school claimed those who did not fit established educational models, who were too revolutionary, non-American, interdisciplinary, unorthodox, wayward or weird to find a home in more august educational structures. And yet it is still an institution that sets and follows norms. The New School is, at its heart, a contradiction: at once an intricate and disorderly bureaucracy, a monolithic institution and a scrappy insurgency, a venerable newcomer, an official dissident. Perhaps its inherent tension is what makes The New School a site of possibility, which is also always the site of inevitable failure. It is where we crouch in the crevices of power: where we are complicit and compromised, within and against, always ambivalent, unable to resist, and resistant nonetheless.

In the manner of a paradox, In the Historical Present stages a call and response with the school’s many pasts. Some of the works in this exhibition trace how the past lives now and others hint at possible futures. Shevaun Wright renders an erased clause in a contract in neon light and opalescent paint; Daniel Bejar repurposes the title of an exhibition staged at the school decades ago alongside the political slogan of an unsuccessful presidential candidate; Sue Jeong Ka repairs books that will be donated to the New York Public Library’s branch on Rikers’ Island to mark complex real estate connections between The New School, the New York Public Library, and municipal prisons; Lucia Cuba takes slogans that might appear on protest placards and makes them into colorful garments; Jonathan Gardenhire pays homage to a work in The New School’s collection that he would pass en route to class every day as a student; Sheila Bridges paints test swatches of shades with titles like ‘white supremacy’ and ‘all white jury’ to draw attention to the political implications of the ubiquity of white walls; Matthew Jensen catalogues the street trees within The New School’s urban radius; Caroline Woolard creates a game that facilitates and troubles institutional meetings using conflict resolution techniques; Nikita Gale edits together recordings of lectures at The New School, marking that which is left unsaid in formal discursive settings like the classroom or lecture hall; Black Lunch Table hosts two roundtables and a Wikipedia edit-a-thon to correct racist blind spots in the public domain; Camilo Godoy dances in the Orozco room to foreground the historical entanglements of José Limón and soft power; Domestic Performance Agency hosts a closing event building upon John Cage’s experiments with mycelium. Together these works do not form a coherent structure. Rather, they enter into an inconsistent, polyvocal conversation–with one another and with the university’s many pasts.

Photographer unknown, The Mobilization for Real Diversity, Democracy, and Economic Justice, c 1996-1997, Carmen Hendershott collection of New School ephemera. Courtesy The New School Archives and Special Collections.

Tenses

The historical present (also known as the narrative present) is a tense form that denotes a way of speaking as though the past were happening right now. Tenses are a way that we locate action in time. Tenses are verbs and verbs are tense. Verbs are tensile. Tense is a tool, a weapon, and a trap. The word ‘tense’ also refers to the state of tension. The two meanings don’t share an etymological root–one comes from the latin tempus, meaning "a portion of time" and the other from the latin tensus, past participle of tendere, meaning "to stretch, extend." And yet the latter definition holds promise for this exhibition–for stretching and extending is what we are doing when we look back at the past or forward into the future. Tension can mean a state of balance between contradictory forces, and from tensions we also get the metaphoric possibility of ‘tensile’ meaning that which bends and flexes, the material property of sustaining without breaking under pressure.

Scripts and scores

The New School’s archive holds papers from faculty, trustees, staff and students. Among these documents is a pair of ‘scripts’ collected under the moniker ‘Changes in the weather.’ The ‘Orientation Disruption Script–Spring 1990’ calls attention to violence on university campuses, naming specific dates and places of racialized, gendered and queer-phobic violence. It is an historical document that has lost none of its urgency in the intervening three decades. Its relevance to the present moment is at once disheartening and hopeful: things have not changed (much), but the archive contains tools and strategies for change.

Archives are more than accumulations of paperwork; they can be immaterial–living in gestures and performances learned by heart through daily repetition. Martha Graham (who worked within The New School’s 66 West 12th Street building in the 1930s) wrote that “we learn by practice. Whether it means to learn to dance by practicing dancing or to learn to live by practicing living, the principles are the same.” This exhibition considers the ways we move through and within institutions as a practice of personal and social choreography.

Institutions require protocols, procedures and norms to operate, and this institution is no exception: while in many ways The New School’s founding was a rupture of such procedural norms, its protocols nevertheless entrench past behaviors to ensure (and sometimes imperil) operational survival. The calling of meetings, writing of curricula and syllabi, scheduling of classes, refinement of grading systems, keeping of office hours, planning of lectures, printing of posters and staging of commencement ceremonies–these and thousands of other procedures can be understood as scripts that, repeated ad infinitum, become second-nature.

All institutions tend, by their very nature, to calcify even as they sustain. With significant caveats and a healthy suspicion of the institutional space as a whole, Meaghan Morris notes that “the English verb ‘to institute’ can mean ‘to start’. More exactly, though, it means to ‘to set up’, to ‘establish’, and these words combine the sense of activity and movement with that of ‘settling’, or ‘putting in place’. Institutions are ambiguous: enabling action, they also stabilize and constrain.” This ambivalence towards institutions as sites of both sustenance and constraint permeates this exhibition. If, in the century that this exhibition marks, artists have pushed up against institutional boundaries, they have also sought to harness institutional procedures to redirect their resources. Several works in this exhibition call upon audiences to be active participants rather than passive observers. Inviting audiences to participate in workshops, programs, and process-based collaborations, they lay out systems that nurture audience participation. These works only comes into being in the encounter between artist and audience, just as the university only comes into being through its student body.

Daniel Bejar, Rec-elections (Don’t Say You Don’t Remember.) 2019. Vinyl text. Courtesy the artist.

Daniel Bejar

Rec-Elections (Don’t Say You Don’t Remember) re-animates a political slogan from the 1970s, drawing out the productive ambiguities of language. ‘Don’t say you don’t remember’ is written in monumental letters on the wall at the entrance of the gallery. On a window facing West 13th Street are the words ‘My God! We’re Losing A Great Country.’ These two phrases, which intersect if viewed from the right angle, were spoken three decades ago; one on senator George McGovern’s 1972 campaign poster, and the other the title of an exhibition organized by New School students in 1970 during the nationwide student strike responding to the Kent State shootings. They are connected through a single image—the infamous photograph of a woman kneeling beside the body of a student slain at Kent State in 1970, which appeared on McGovern’s campaign poster, and on the cover of the exhibition’s catalogue. Neither phrase has aged; indeed they take on new urgency in the present political climate.

Daniel Bejar’s work exploits double meanings and repurposes political and marketing messaging to critique the social structures that we inhabit. Through photography, installation, performance and web-based platforms, he challenges the politics of site and bodies to reveal social power imbalances. He has exhibited internationally in public projects and exhibitions at internationally in public projects and exhibitions at the Brooklyn Museum (New York), The Drawing Center (New York), Smack Mellon (New York), SITE Santa Fe (Santa Fe), Peripher Gallery (Zürich), among others.

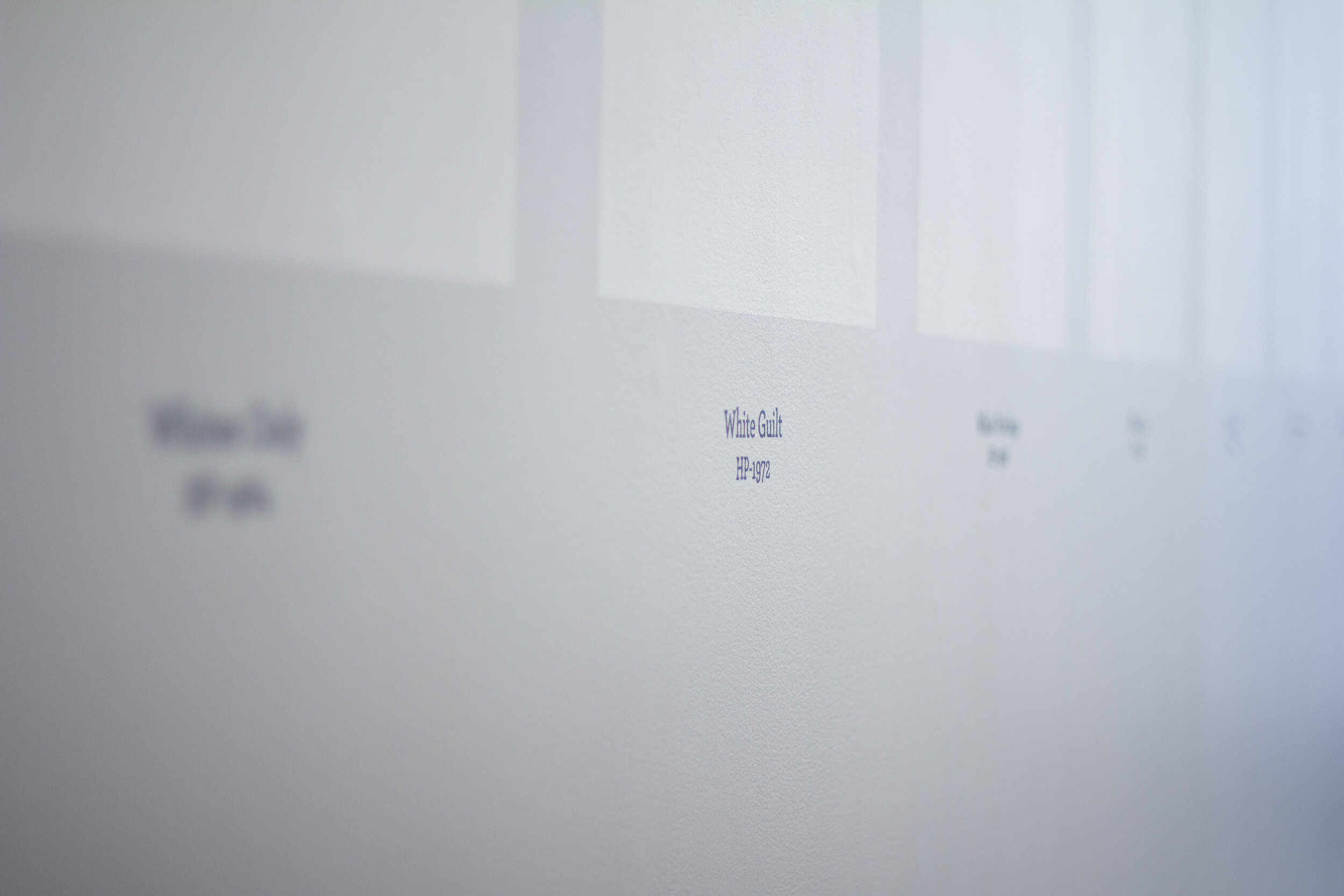

Sheila Bridges, 19. 2019. Site-specific installation and limited edition artist’s book (edition of 1000). Courtesy the artist.

Typically positioned as a neutral backdrop, white paint does ideological work—inasmuch as it lays claim to a fictional neutrality —in galleries, domestic interiors and perhaps most importantly, educational institutions. In an essay on white paint, New School faculty Wendy Walters writes that “Here the argument might cite the resolution in policy as evidence of the fading relevance of white lead to the present moment. After all, history is not the present moment. But then again, of course it is.” In this work interior designer Sheila Bridges ponders what would happen if shades of white house paint were titled variations on ‘White Privilege’ or ‘All White Jury.’ 19 white paint swatches chronicle American whiteness over the past century, with each swatch referencing moments from President Woodrow Wilson's advancement of Jim Crow laws, the same moment at which The New School was founded by five white men, to the presidency of Donald Trump with its tacit appeal to white supremacists. Across from this installation, Glenn Ligon’s Untitled (I feel most colored) (1992) borrows phrases from Zora Neale Hurston—“I feel most colored when thrown against a sharp white background”, and Ralph Ellison—“I am an invisible man.” Triangulating this conversation, David Hammons’ African American Flag (1989) replaces the red white and blue of the United States flag with the Black Nationalist colors red, black, and green, reflecting the symbolic potential of color.

An alumni of Parsons School of Design, Sheila Bridges founded her own interior design firm in 1994. She has been named “America’s Best Interior Designer” by CNN and Time Magazine and has authored two books: Furnishing Forward: A Practical Guide to Furnishing for a Lifetime, which was released in 2002 and The Bald Mermaid, A Memoir, published in 2013. Her works often blur the boundaries between art and design. In addition to her many accolades as an interior designer, her work is represented in the Smithsonian Cooper-Hewitt National Design Museum’s permanent wallpaper collection and the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture.

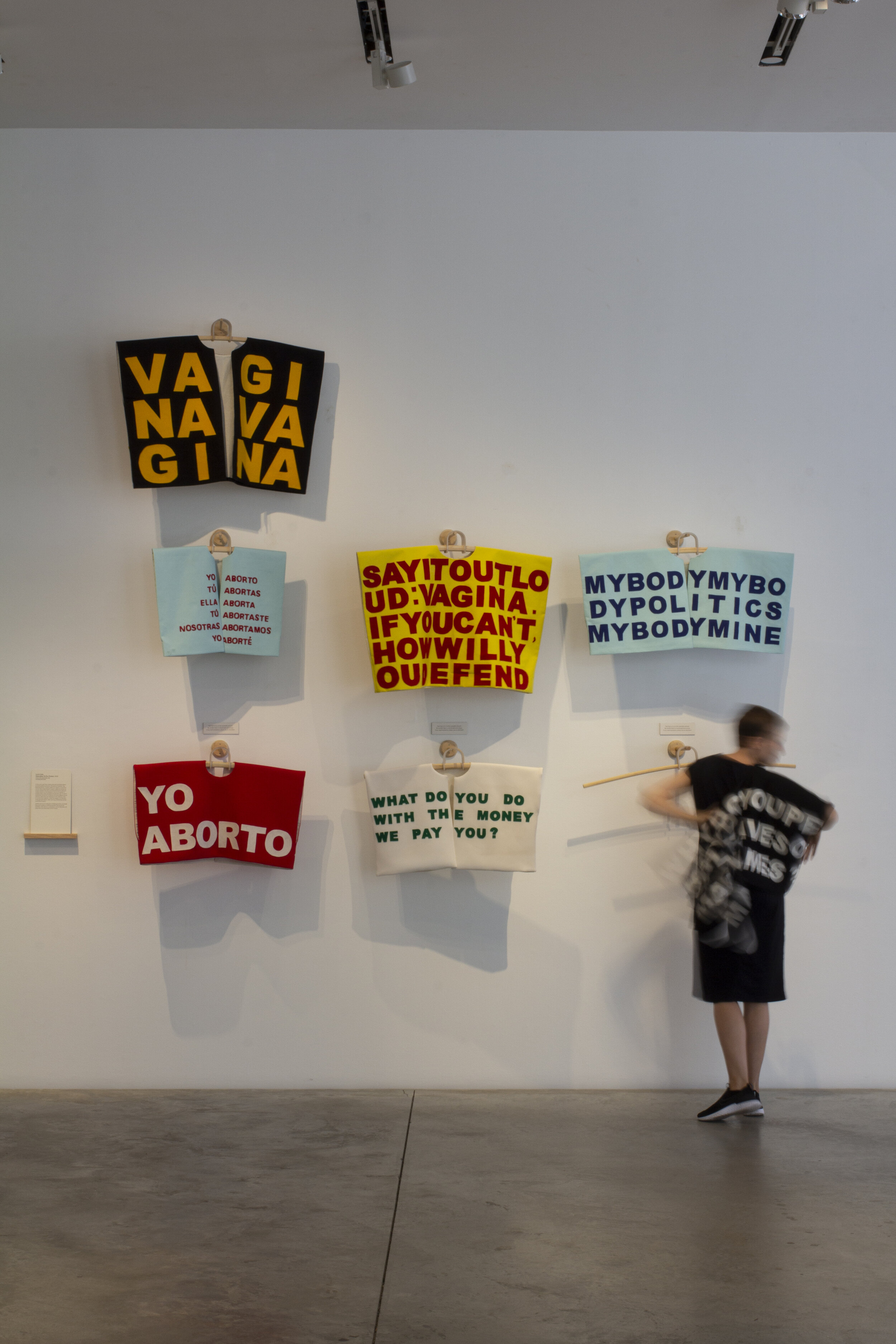

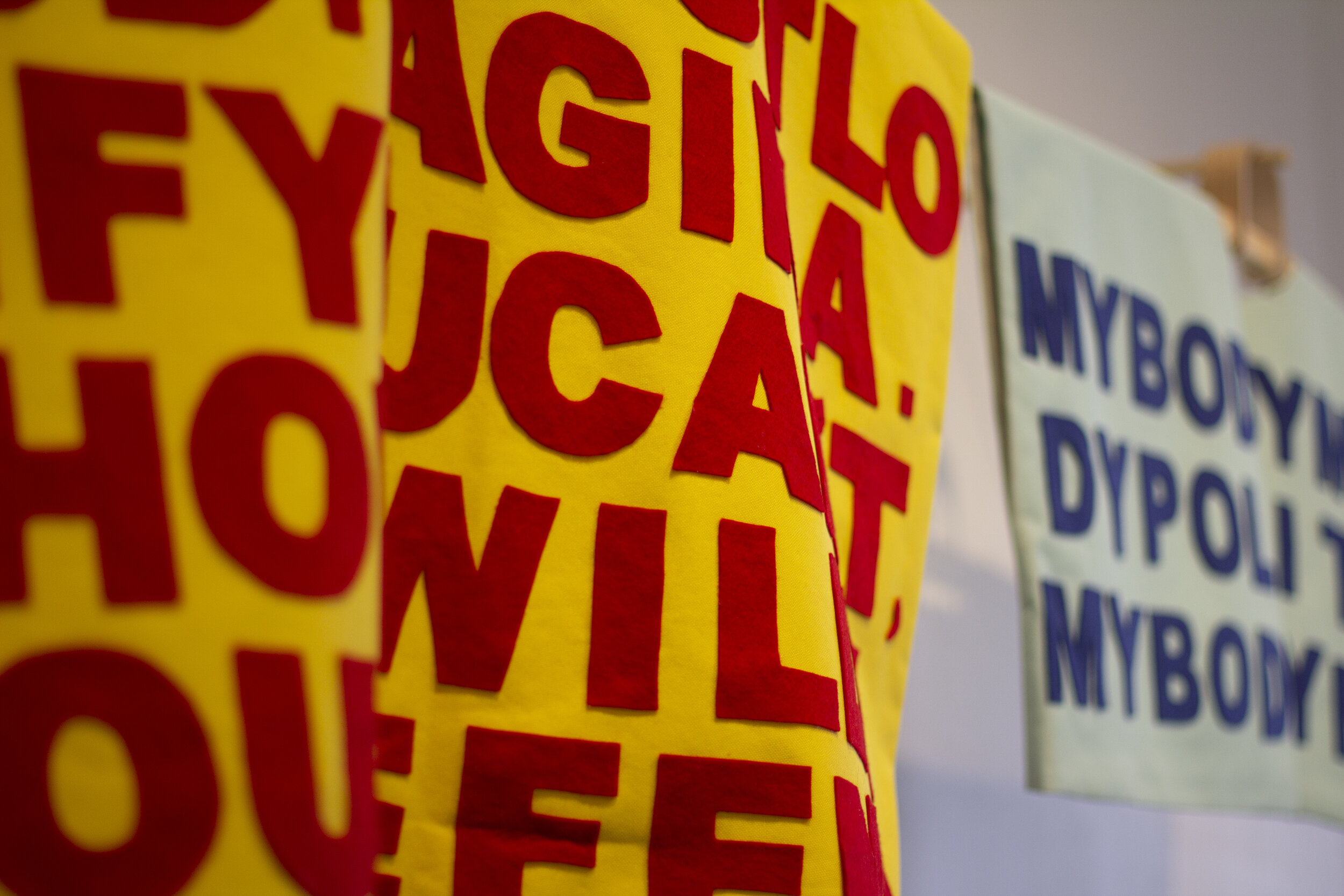

Lucia Cuba, Wearables To/For Protest. 2019. Hand-sewn garments, felt. Courtesy the artist.

For this exhibition, Sue Jeong Ka has established a partnership with the Jefferson Market branch of the New York Public Library. Until 1945, the building was used solely as a courthouse. Their neighbor organization, Jefferson Market Garden is built on the site of the Women’s House of Detention, which operated until the Correctional Institution for Women was moved to Rikers Island between 1971-1974. In the 1970s, The New School attempted to acquire the site to house their burgeoning Center of New York City Affairs, which would have included an annex of Jefferson Market Library on the ground floor. While this arrangement never eventuated, the attempt reveals the complex interplay between public and private institutions; between libraries, universities and prisons. Ka’s work touches on the inherent tensions between the hospitality of public spaces, the covert institutional complicity of municipal services, and the property market. Such organizations have very different agendas that are nevertheless structurally connected. Her work consists of a book in which she reproduces the archival materials documenting this history, accompanied by a conversation with NYPL librarian Andrew Fairweather about the library’s potential hospitality. Throughout this exhibition, Ka will repair books withdrawn from circulation in the New York Public Library; these will be sent to the library at Rikers Island. A multi-faceted project that spans material and social practices, this piece opens doors to a variety of conversations, and resists definitive answers. Alongside Ka’s work is a piece by Sable Elyse Smith drawn from The New School’s art collection. A poetic meditation on the violence of the carceral system, this letterboard reflects on the artist’s experience visiting her father in prisons over the past 20 years.

Sue Jeong Ka’s work seeks to meet communal needs. From commemorations of female Asian immigrants from the 19th century to a trilingual community newspaper and a piece assisting queer and immigrant homeless youth in New York apply for federally issued ID, her artwork seeks to mobilize traditional art spaces for community services and in so doing, critique the public structures in which we exist. She is an alumna of the Whitney Independent Study Program (New York) and a recipient of the 2018 NYSCA/NYFA Artist Fellowship, the Create Change Fellowship, artist in residence at The Laundromat Project (New York), the Studio in the Park, Queens Museum/ArtBuilt (New York) and The Drawing Center (New York).

Nikita Gale, CHECKING. 2019. Sound and video installation. Courtesy the artist.

For this exhibition, Nikita Gale searched within The New School’s archives for texts, ephemera, class lectures, notes, and media recordings with any mention of the word “silence.” She found two videos of conversations held at The New School addressing the language used within social and political debates, as well as the role of women in journalism (speakers included Svetlana Mintcheva, Leslie Camhi, Mary Miss, L. Somi Roy, Jill Scott and Robert Atkins). Though these recordings were catalogued in the archive, their actual contents were unknown until the artist commissioned digitized versions. Gale has edited the audio from these discussions and created a script using transcribed portions of the talks - presented as a spatialized audio work played back on a directional speaker. Gale’s process in this work uncovers the often hidden and buried nature of archival materials, and how information and ideas, though documented, still have the possibility to be kept silent and hidden. The New School, with its many programs, student and faculty organizations, and informal collectives, maintains a poly-vocal conversations that overlap and, as a result, are often drowned out. Through this work, the artist expands the meaning of silence beyond a lack of sound, exposing the institutional process of muffling or concealing that happens within systems of documentation and dissemination. Nikita Gale explores objects as tools for interrogating social, political, and emotional space. Often working with sound and the objects that either produce or muffle noise, Gale creates discursive pieces that propel a deeper look into how patterns of thought and behavior are reflected in the material remnants of our world. Gale holds a BA in Anthropology from Yale University and an MFA in New Genres from UCLA. Her work has been shown at the Hammer Museum (Los Angeles), The Studio Museum in Harlem (New York), Commonwealth and Council (Los Angeles), CUE Foundation (New York), 56 Henry (New York), among others.

Camilo Godoy, Rehearsal for Diplomacy, June 2019. Courtesy of the artist.

For this exhibition, Camilo Godoy stages performances and dance workshops that complicate dancer Jose Limon’s legacy in the context of the State Department’s support of his work during the Cold War Era. Calling attention to the power dynamics set in motion by this institutional support of Limon’s work, Godoy reveals the ways that politics and Queer Latinx identities have been have been systemically de-emphasized in Limon’s work to fit within the official, heteronormative and hegemonic portrait of the United States at the time. Through performed actions, reading of texts, and participatory workshops, Godoy reconstructs this history in a site-specific context, the Orozco Room, itself a conflicted set of political symbols and historical juxtapositions. The room is named for a mural painted there by Jose Clemente Orozco, which was one of the first site-specific artworks commission by The New School. Completed in 1931, the frescoes depict modern political and social revolutions that defied enslavement and oppression around the world, along with idealized scenes of universal brotherhood and labor, both intellectual and physical. In the 1950’s, the section depicting portraits of Vladimir Lenin and Joseph Stalin was covered with a yellow curtain after complaints and pressure from both within and outside the The New School community. These objections were set amidst the backdrop of the anti-Communist McCarthy era. While Limon was traveling the world promoting United States arts and culture, Orozco’s murals were partially visible, succumbing to political pressures of Cold War-era New York City. Godoy’s performances and workshops explore Limon’s techniques of falling. Dropping to the ground is a tactic for subtle, personal uprisings; responding to failed interactions in the course of a day, it is a metaphor for navigating institutional and international political pressures. Camilo Godoy’s multidisciplinary practice considers performance and performativity as a means to deconstruct social and political frameworks. Incorporating research and process-based collaborations into his performances he invites a critical look into the narratives and experiences that are left in the margins of our cultural histories. An alumni of Parsons and Lang, Godoy’s work has been featured at the Brooklyn Museum (New York), the Whitney Museum of American Art (New York), CUE Art Foundation (New York), Recess (New York), and coleção moraes-barbosa (São Paulo), among others.

Caroline Woolard, The Meeting (Installation View). 2019. Laminated walnut with satin finish, nylon net, foam, mycelium, glass, wooden spheres. Courtesy of the artist.

Sometimes meetings are vibrant exchanges. Sometimes they are a bureaucratic chore. Occasionally they are tense stand-offs—a conflict zone. The New School has been a site of thousands of meetings between artists working together across disciplines. Born out of the artist’s experience at The New School as adjunct faculty, The Conversation Game honors the many collaborations that have been hosted by this institution, from John Cage’s mushroom class in 1959 to Jean Gardener’s ‘threeing’ practices (which continue to be shared and used in informal networks of faculty at the New School) and Sekou Sundiata’s America Project. And yet The New School is not a utopia of collaboration; only 19% of New School faculty are employed on a full-time basis and adjuncts’ economic precarity shapes pedagogy and interpersonal relationships within and beyond the institution. With this work, Woolard asks how the New School might support research about equity and cooperatives while maintaining inequitable labor conditions for faculty. The piece occupies three spaces: a wall of the gallery, the conference room adjacent to the gallery, and the office of a staff member and curator at The New School. In the conference room, where the artist herself has often attended meetings and nurtured collaborations, a collection of objects come to life as part of an evolving game. Spheres made from timber and glass can be rolled across the table from one participant to another during a meeting. Their circulation on the table both facilitates conversation, and reveals the power dynamics that underpin institutional meetings. The room remains a working meeting space throughout the exhibition; anyone who uses it can use the tools that the artist has installed there. Indeed the game will evolve throughout the exhibition in response to user feedback. In playing on the institutional script of the meeting, Woolard proposes strategies for collaboration that nevertheless raises the issue of adjunct labor within a hierarchical power structure. Woolard’s practice spans sculpture, installation, performance and pedagogy and includes barter networks and collaborative educational models. She is the co-founder of barter networks OurGoods.org and TradeSchool.coop, the Study Center for Group Work, BFAMFAPhD.com, and the NYC Real Estate Investment Cooperative. Her work has been commissioned by MoMA, the Whitney Museum, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Creative Time, and the Brooklyn Museum, among others and has been written about in The Brooklyn Rail, Artforum, Art in America, and The New York Times.Making and Being, her forthcoming book about interdisciplinary collaboration, co-authored with Susan Jahoda, will be published in the fall of 2019.

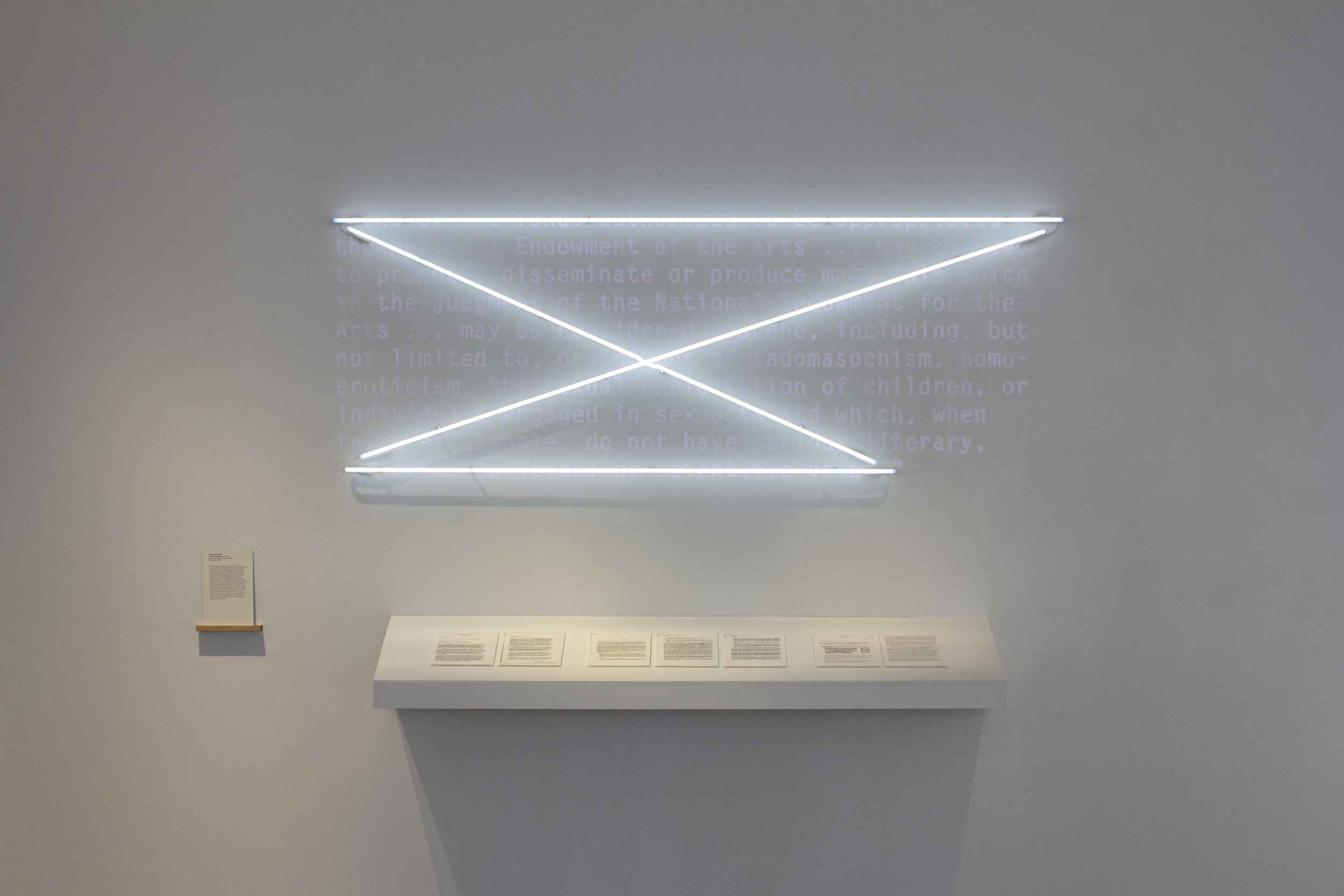

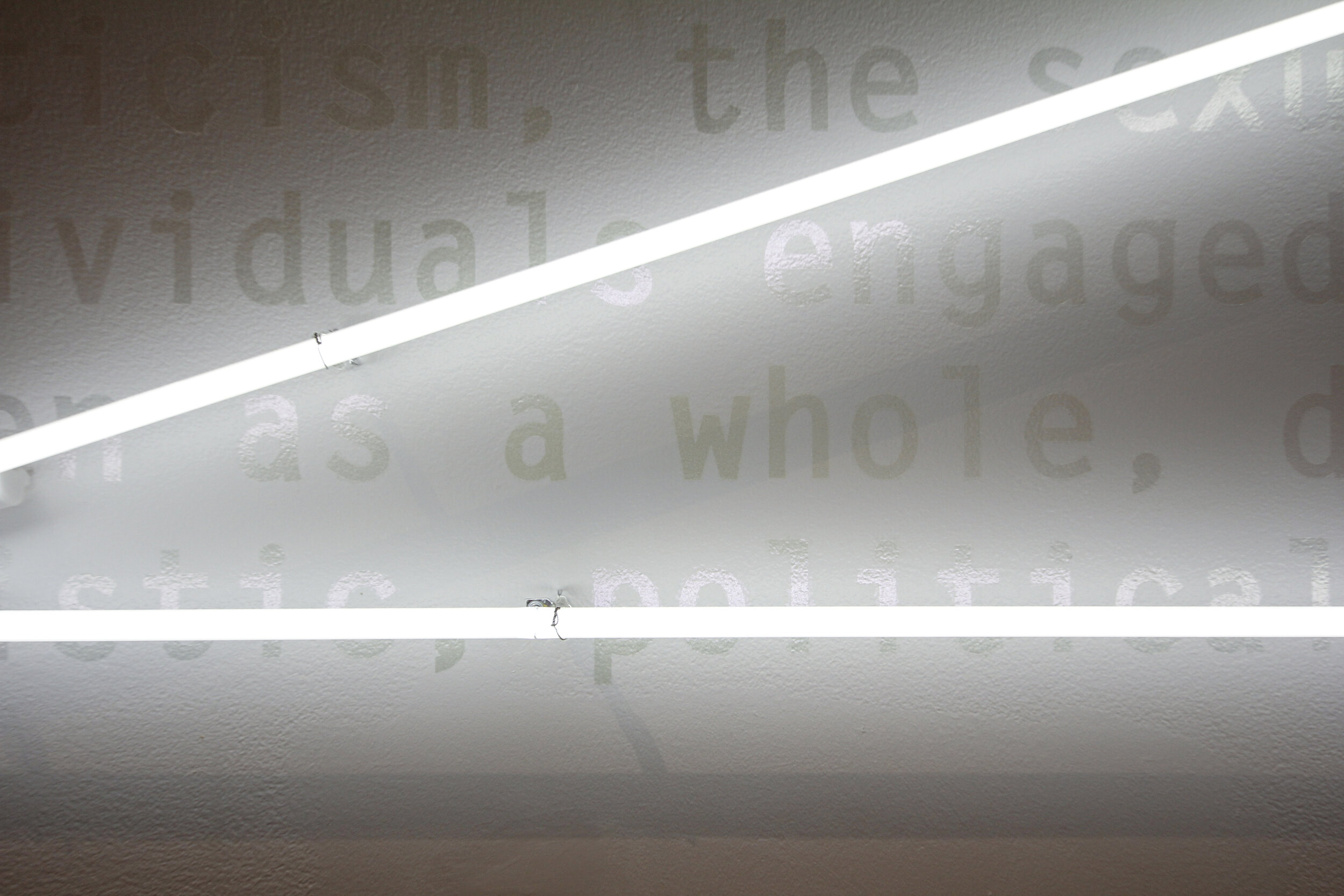

Shevaun Wright, Double Redaction (detail). 2019. Paint, neon light, archival documents. Courtesy the artist.

Shevaun Wright draws our attention to a history of litigation. In 1990, The New School sued the National Endowment for the Arts to remove an obscenity clause put in place during the ‘Culture Wars’. The clause—which draws a false equivalence between obscenity, homoeroticism, and child pornography—responded to was put in place following two controversies surrounding NEA-funded projects in 1989: a retrospective of Robert Mapplethorpe’s work that included homoerotic photographs, and Andres Serrano’s infamous ‘Piss Christ’. The artwork for which the school received funding—a collaboration between the artist Martin Puryear and landscape architect Michael Van Valkenburgh—was not impacted by the clause. The New School was one among several institutions that contested it on the principle of freedom of expression. Inscribing this clause on the wall, Wright restages its erasure using neon and opalescent paint. A slash of light at once crosses out and illuminates this section, reminding us that while redacted, it remained in the contract ‘under erasure.’ Wright’s accompanying legal advice speculates as to the etymological origins of obscenity, which is said to derive from ‘off scene,’ denoting that which is not on stage. Understanding the university as a platform with the power to include and exclude, she indicts The New School’s historically white and male curricular focus. Perhaps the university’s focus on the lofty ideal of freedom of expression itself left the clause’s target of how eroticism under erasure. Wright is an artist and lawyer. Her work uses the legal contract as a medium to explore the law from a postcolonial and feminist perspective. She addresses themes of sexual violence, institutional corruption, the ongoing effects of colonialism and (drawing on her Australian Aboriginal heritage) critical race theory. She is an alumni of the Whitney Independent Study Program (New York), an Art & Law Program Fellow (New York) and an Australian Cultural John Monash Scholar.

Jonathan Gardenhire, Memoranda/Speculations 1 (I Ain’t Dead Yet, Mother Fucker) (detail). 2019. Digital chromogenic prints. Edition of 3 + 2APs. Courtesy the artist.

Jonathan Gardenhire’s installation pays homage to a work in The New School’s art collection. Gardenhire first encountered Glenn Ligon’s diptych Condition Report (2000) in the corridor of The New School en route to class. Ligon’s piece, which is an etching of his earlier painting with a conservator’s annotations, replicates the sign worn by striking sanitation workers in Alabama during the Civil Rights Movement. Taken out of context, the phrase ‘I AM A MAN’ can mean many meanings; for Ligon, the condition report’s documentation of damage and decay signaled the passing of time and with it, the ongoing negotiation of civil rights legacies. For Gardenhire, the question of race and masculinity resonates in this piece, and his own photographic practice reflects a deep engagement with portraiture that pulls the moniker ‘man’ into a personal focus. In these thick accumulations of research materials, reproductions of Condition Report appear alongside photographs and texts by Thelma Golden and Henry Louis Gates, Marvin Gaye, bell hooks, Langston Hughes, Robert Mapplethorpe, David Marriott, Herman Melville, Walter Mosley, Walt Whitman, and Richard Wright among others. The artist notes that, coupled with pornographic images (some of which are appropriated), a tenderly inverted portrait and a smile sporting grills—the last photograph that the artist took as a student at Parsons—they “become like a muscle with a peculiar role in the larger body or constellation.” This orrery shows the material practices of citation and the public life of Black male embodiment; is “history [as] not only what hurts but what arouses, kindles, whets, or itches.” Gardenhire is a photographer and cultural producer whose work considers the erotics of Black masculinity and questions of value and commodification. He is a graduate of the photography program at Parsons School of Design where he worked under the tutelage of Bill Gaskins and the late photographer George Pitts. His work has been shown at Aperture Foundation (New York), Medium Tings (New York), the Slought Foundation (Philadelphia), among others.

Lucia Cuba, Wearables To/For Protest. 2019. Hand-sewn garments, felt. Courtesy the artist.

They are on the body and about the body–about the constrictions of gender norms, the stigma of female anatomy, the control of reproductive rights, the unwillingness of institutions to pay for healthcare or childcare. Many of these pieces are in Spanish, and playfully exploit the political possibilities of its grammar. In one piece, Cuba plays on the Spanish form of abortion: while the English word ‘abortion’ is a noun, the Spanish ‘aborto’ is a verb. Conjugating the verb across the opening of a tunic, Cuba slips between agencies. This exhibition includes eight garments, several of which can be tried on. While from a distance they resemble banners held aloft in a protest, wearing them reveals the intimacy of garments and stories they tell. An alumni of and faculty at Parsons School of Design, Lucia Cuba is a designer, textile artist and scholar based between New York and Lima, Peru. She approaches fashion as a political and performative device, exploring how it can expand beyond commercial and aesthetic contexts. Cuba’s work engages with textiles and wearable forms as objects that convey political, social, environmental, and public health issues. Cuba’s work has been exhibited at the Museum of Arts and Design (New York), BRIC Arts Media (New York), Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen Museum (Rotterdam), Museo Amparo (Puebla), OCT Art & Design Gallery (Shenzhen), ART LIMA (Lima), among others.

Yonkers International Press, The Book is Someone to Touch. 2019. Performance. Courtesy the artist.

In The Book is Someone to Touch, Yonkers International Press brings together the disciplines of dance and publishing to show the intimate choreographies of holding, reading, writing, coding and printing. Reflecting the history of dance and its challenges with documentation, this work simultaneously engages with and resists the archive. The artist asks what, if anything, of movement can be captured in the archive, and what does an archival impetus do to movement? For In the Historical Present, YIP is creating a course reader collating writing by students and professors, transcripts of chat-room conversations, materials gathered on forays around the school, and whatever gallery visitors choose to scan. Seeking to capture the movements of and through this exhibition, it will be a running commentary, a container to catch the spillage of what cannot be recorded contained in the exhibition and its catalogue, a register of bodies moving through the space of the gallery. In September and October, Yonkers International Press will host workshops writing, performance and publishing workshops.

Benjamin Van Buren is a graduate of Lang’s Arts In Context program with a focus on dance and philosophy, as well as an alumna from The New School for Social Research with an MA in Liberal Studies. He founded Yonkers International Press (YIP) as an experimental publishing house that archives and re-disseminates materials collected at live performances and dance festivals.

Domestic Performance Agency

Domestic Performance Agency (DPA), led by Athena Kokoronis, is an open and process-based platform foregrounding the often hidden, ephemeral labor of hospitality, and the social dynamics that underlie the daily tasks that maintain our domestic spaces. The artist has prepared a meal that is shared with the exhibition’s visitors during the closing reception, which is the culmination of a process of mushroom cultivation and collaborative conversations with New School Sustainable Design faculty Jan Mun and Christopher Lee Kennedy, whom Kokoronis met on mushroom foraging expeditions to search for and cultivate fungi growing on the natural surfaces of city life like trees and grass. This collaboration calls back to John Cage’s experimental pedagogy at The New School in the 1960s, when he led students on mushroom hunts. Mycelium grow upon vegetables, producing mushrooms and other edible fungi, a network of intertwined growths that depend on their proximity and ability to mix with one another. Here mycology becomes a vector for interconnected social life, a point of departure for hospitality. Instead of depicting the collaborative process through objects, DPA serves its result to the audience, privileging the audience’s experience over the gallery’s orientation towards fine-art objects.

Domestic Performance Agency (DPA) is the name and space of Kokoronis' current choreographic process exploring aspects of performance production, curation, food, clothing, and searches for the creative economy within these realms, which begins and extends out of domestic scale with hospitality. DPA Soup Subscriptions, for example, fun year round. DPA has collaborated with Jasmine Hearn, Tatyana Tenenbaum, Jessie Young, Angie Pittman, David Thomson, Marion Spencer, Tyler Rai. Athena Kokoronis published CookBook Domestic Performance Agency with Yonkers International Press (YIP) in conjunction with the Dance & Process series at The Kitchen in 2018. A second edition will come out in Fall 2019 in conjunction with In the Historical Present. DPA is also represented by the Lydia Rodrigues Collection (LRC).